In first grade, there was an assignment where we had to explain the origins of our names. I remember sitting in a circle as each student got one minute to share. With the gravitas of these pitches, each one outdoing the next, you’d have thought we were fighting for deals on Shark Tank.

“I’m Kenneth Langley the Second. I was named after my great-grandfather’s best friend, who died with him in the War.”

“Which war?” I asked.

It didn’t matter. It was enough (or Kenough, I should say) to make our teacher reach for her handkerchief and dab her eyes, signaling to the class that it was time to collectively emote.

When my turn came, I said what I’d been told: “My mom picked it from a name book.” Instead of the anticipated gasps and handkerchiefs, all I got were blank stares. Down came the instant regret for not jazzing up my story. I’d missed the chance to wield the power of a white lie – a skill I’d already begun learning by this age to dodge my parents’ cruel and unusual punishments. While some Asians were getting their headstarts in snowboarding or figure skating at 6 years old, for me, it was lying.

Not only did my story pale in comparison to Kenneth’s wartime saga, but I simply couldn’t compete with the kids also flaunting middle names. These received reactions like, “Rose, like the flower? Oh, that’s pretty.” I couldn’t even tell you what a middle name was (still can’t, TBH). Being the attention whore I was, I was determined to rectify this.

I went home that night and tried to pry some sentimentality out of my mother.

“I picked Alina from a name book,” she said again.

“And???” I asked.

“Well, I flipped to the page with the girl names that started with A, and there it was.”

After some more probing, she eventually told me that when she was a student in China, since her first name commenced with a “Y,” she was always called last in roll call. So, she didn’t want her kids suffering the same fate. As a therapized person, I totally understand making parenting decisions based on past traumas. But there, I broke it to her: “In the spirit of great American equality, we go by our last names here, Ying. And since my last name begins with a “P,” alas, I’m still in the latter half of roll call.” (I wasn’t nearly this eloquent as a 6-year-old, but you get the idea). As much as Chinese people had a reputation for being intelligent, this was a system you couldn’t outsmart.

My seemingly unremarkable name occasionally leaves me feeling detached. Whenever I find myself staring in the mirror longer than usual, I start wondering, “Do I embody the essence of an Alina?” which will then prompt me to say to my reflection, “Hi, I’m Alina.” It’s a quirky routine so I can register if my name matches my looks, and vice versa. I’ll repeat it over and over until I reach the point of dissociation and actually feel like I’m perceiving myself from another person’s perspective. Any passersby might have thought I was casting a Bloody Mary spell, but in my mind, this was akin to a YouTuber practicing self-introductions on camera.

Among my friends, I’ve earned a reputation as a people pleaser (albeit on the path to recovery). They say I forgive easily because I have a high level of empathy, but really, I just find it unbearably uncomfortable when others are upset with me. Recently, I stumbled upon a TikTok discussing the Kiki and Bouba effect in linguistics, which categorizes words as having a jagged “kiki” or a bulbous “bouba” shape. Psychologist Wolfgang Kohler studied this phenomenon in the 1920s, using fictional words “takete” and “maluma.”

Care to guess which is kiki and which is bouba, my little ones? (Just checking to make sure you’re still here. Also, having parents who attended and still to this day brag about grad school, this is the closest I’ll get to experiencing their TA high, so let me live).

“Alina” sounds undeniably bouba-esque to me. In this TikTok, the user also said there was a recent study where people associated the name “Molly” with a rounder feeling and “Kate” with a sharper one. In short, different names give off different vibes. This leads me to wonder if people are treated any differently because of their names. Is my inclination to please people somehow tied to being named a bouba and not a kiki? If I were a Maxine, a Candice, or a Gretchen, would I have refrained from groveling at others’ feet and instead experienced them groveling at mine? Could I have cared less about sparing people’s feelings and been making more shit that I wanted to happen in life? (But then again, Gretchen didn’t make fetch happen, so maybe this theory doesn’t hold up.)

My family took a trip to China this past November, where my dad said that he wished he’d let my unofficial Chinese name, “Songyuan,” be my U.S. government name. He believed it would have prevented me from whitewashing and preserved my uniqueness. (Perhaps it was no coincidence that he voiced this sentiment right after witnessing my cringe-worthy attempts to speak Mandarin with my relatives). With each passing year comes the gradual fading of my Mandarin proficiency and an increasing awareness of how distant I am from my Chinese roots. So maybe he’s got a point about the whole cultural preservation thing. But as far as uniqueness goes, I feel decently content with Alina. It, at least, spares me the fate of being another Asian Annie or Angela. (Also, could someone let me know why Kevin is so ubiquitous? Was there an Asian person convention that my parents missed the invite to? When my brother was born, they named him Alvin because they enjoyed the 80s television series “Alvin and the Chipmunks.” Seeing the 2007 live-action film version was like seeing God to them.)

Yet every time I consider Alina Peng to be a tad unique, I am quickly humbled by the dazzling names of celebrity offspring: North West. Blue Ivy. X Æ A-Xii Musk. In another life, I would like to be named AḸ-ii⒩ⓐ Peng.

I suppose how distinctive my name is doesn’t really matter because being a minority in this country means I still get misrecognized based on my face. That same first grade teacher, after spending four months learning our names, still managed to confuse me with [REDACTED], another Asian girl in the class. As a child, when everything felt personal, experiencing identity erasure like this was profoundly disheartening.

But I recently looked that teacher up online (in true Gen Z fashion) and discovered that she’s now 87 years old. Without revealing my own age, that put her well past the average U.S. retirement age of 61 when she taught me. So, I’ll cut her some slack. Whether she harbored racial biases or was simply grappling with senility, I won’t ever definitively know, so I’ll give her the benefit of the doubt. Perhaps it was a mix of both.

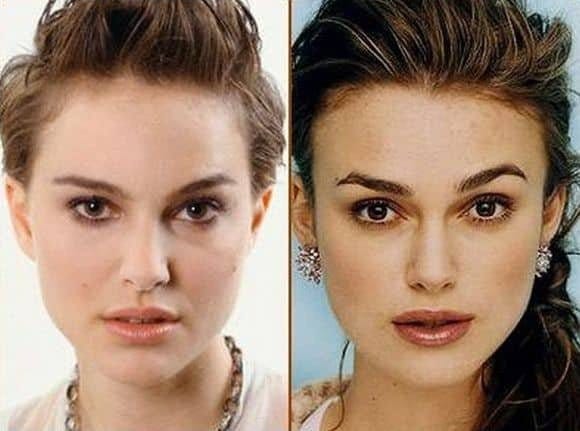

Call it karma for my fatal flaw of not being able to tell Keira Knightley and Natalie Portman apart.